In Lincoln’s fight with ash borer, 3,000 trees removed, nearly 2,000 treated | Local

Four years after the emerald ash borer was found near Lincoln, the city’s battle with the tree-killing bug wages on.

Here’s an update from the front lines:

Tree removal: The city has removed about 3,000 of the 14,000 public ash trees that line Lincoln’s streets and are scattered throughout its parks and golf courses — including 360 so far this fiscal year.

It’s fallen more than 100 trees short of its goal of removing 800 public ash trees annually the past couple of years, but its forestry crew was still busy.

For instance, in 2020, it faced a half-dozen back-to-back storms that did significant damage to all types of city trees, not just ash.

“And we spent a lot of time doing cleanup that year,” said Lynn Johnson, director of the city Parks and Recreation Department. “When that happens, it’s all hands on deck.”

The city normally removes 800 non-ash trees per year; in 2020, it removed nearly 1,800.

People are also reading…

Treatment: The city saw the Asian insect coming. After it was detected in North America in the early 2000s, it started marching west, killing tens of millions of ash trees.

Lincoln drew a hard line at first, planning to remove every public ash tree in its city limits.

But it added a second strategy a couple of years ago, and began treating its trees with a chemical that can prolong their lives.

Bug wars: Feds introduce Asian wasps to battle emerald ash borer outbreak in Lincoln area

It set a goal of treating 1,700 eligible trees a year. Those getting stays of executions must be viable — relatively young but big and strong — or in significant locations, like the five towering trees that shade Witherbee Park near 46th and O streets, or the autumn purple ash that line a stretch of Goodhue Boulevard south of the Capitol.

The city plans to treat the trees every three years, allowing it eventually to extend the life of about 5,000 trees that otherwise would have been cut down.

During its first-year pilot program, it treated about 350. Last fiscal year, it treated 1,349.

The city is also continuing its Adopt-An-Ash Program, which allows homeowners to privately treat eligible public trees along the street in front of their homes. But it wants to know who’s helping so it doesn’t inadvertently cut down a treated tree. Learn more by going to trees.lincoln.ne.gov and clicking on Adopt-An-Ash Program.

The replacements: The city plans to replace each ash it takes out, and offers vouchers to homeowners to pick out and plant an approved species.

It worked two years ago, when more than 800 replacement trees were planted. But last fiscal year, just 237 were replaced.

And they’re learning that number hinges on the socioeconomic status of a neighborhood. Higher-rental and lower-income areas have been less likely to replace the ash trees the city removes, he said.

Ash borer update: Some trees to get reprieve; replanting plans not taking root everywhere

“Landlords don’t tend to use the vouchers, and if someone’s working two to three jobs, they’ve already got their plate full.”

To change that, his department recently hired a new community forestry planner, who will work with landlords and neighborhood associations — but also coordinate the contracting of the planting where it’s not done voluntarily.

Time taking its toll: And finally, ash borers take some time to kill their hosts, and now that they’ve been busy for a few years, city crews are starting to see more signs and symptoms of damage.

“We’re getting to that point on the curve where we’ll probably see a significant uptick in the number of trees dying.”

Every ash on the map: Finally, the city has plotted every public ash on a searchable map, including those under treatment, and those already removed. To find out if the tree in front of your house is an ash, go to trees.lincoln.ne.gov, click Adopt-An-Ash Program, and then click Public Ash Trees.

The ash borer has landed: First infestation confirmed in Lincoln

‘Each table is a small victory’ — How volunteers and salvage lumber are helping flood victims

Top Journal Star photos for March

Top Journal Star photos for March

A driver in a pickup truck makes their way along a northern portion of 27th street as a break in the clouds after Tuesday’s storm allows for a final burst of color on March 22, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Elton John points to the crowd after he finishes his opener, “Bennie And The Jets,” on Sunday, March 27, 2022, during the Elton John: Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour at the Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraska head baseball coach Will Bolt talks with his team between innings during the baseball game on Sunday, March 27, 2022, between Michigan and Nebraska at Haymarket Park. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Cass Warren, 12, throws a disc golf next to his father Dan Warren on a windy afternoon at Pioneers Park, Friday, March 25, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Theresa Thibodeau, Breland Ridenour, Charles Herbster, and Brett Lindstrom (from left) participate in a discourse during a gubernatorial debate hosted at the Nebraska Public Media studios on March 24, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Lincoln Pius X’s Ellie Wolseger rests on the mat after an attempt in the girls pole vault on Thursday, March 24, 2022, during the Northeast Relays track meet at Lincoln High. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Kindergartener Lyum Brady eats lunch on Wednesday, March 23, 2022, at Hartley Elementary School. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

A Lincoln city crew cleans up a fallen tree near 15th and Sumner streets, Tuesday, March 22, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Cars travel at the intersection of O and 16th streets on a rainy night, Monday, March 21, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

As the sun goes down, fans watch during the baseball game Friday, March 18, 2022, between Nebraska and Texas A&M-Corpus Christian at Haymarket Park. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraska’s Isabelle Bourne and Gonzaga’s Yvonne Ejim dive after a loose ball in the first quarter during the first round of the NCAA Tournament at the KFC Yum! Center on March 18, 2022, in Louisville, Kentucky. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraska’s Griffin Everitt is congragulated by teammates Lei Brice Matthews and Luke Jessen after hitting a 3-run RBI against New Mexico State in the third inning at Haymarket Park on Tuesday, March 15, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Bryan Health staff pray during a ceremony to mark the two-year anniversary of COVID-19 on Tuesday, March 15, 2022, at Bryan East Campus. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraska fans cheer for free T-shirts in the second inning of a game against Omaha on Monday, March 14, 2022, at Haymarket Park. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Malaya Burks (left), 15, plays basketball with his brother DeShawn Burks, Monday, March 14, 2022, at Normal Boulevard & South Basketball Courts. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

The Nebraska women’s basketball team reacts during their bracket announcement Sunday at the Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Elkhorn North celebrates their championship victory over Omaha Skutt after the Class B girls championship Saturday, March 12, 2022, at Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Humphrey/LHF’s Ethan Keller celebrates after his team scores three against Grand Island CC in the fourth quarter during the Class C-2 boys championship at Pinnacle Bank Arena on March 11, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Lt. Col. Christopher Perrone (R), of Papillion, hugs his daughter, Faith, 21, during a welcome home event for soldiers of the Nebraska National Guard’s 67th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade on Friday, March 11, 2022, at the Nebraska Army National Guard base. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Lincoln Lutheran fans react in the closing minutes of the regulation of the Class C-1 girls championship game against North Bend Central, Friday, March 11, 2022, at Pinnacle Bank Arena. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Falls City SH’s head coach Doug Goltz talks to his team between periods during a Class D-2 boys semifinals game Thursday at Devaney Sports Center. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

A pedestrian and a cyclist cross a snowy Goodhue Boulevard on Thursday, March 10, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

People watches the debate to allow concealed handgun without a permit from the balcony, Thursday, March 10, 2022, at Nebraska State Capitol. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Auburn’s Marcus Buitrago (23) tries to control the ball as Fort Calhoun’s Carsen Schwarz (33) dives during a Class C-1 boys semifinal game Thursday at Pinnacle Bank Arena. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraskans for Peace hosts a rally in support of Ukraine on Sunday, March 6, 2022. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Nebraska’s Liam Doherty-Herwitz competes on the still rings during the gymnastics meet between Illinois, Minnesota and Nebraska on Saturday, March 5, 2022, at Devaney Sports Center. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Supporters of the Midwest Freedom Convoy line up along the Superior Street bridge over I-80, on March 4, 2022, in Lincoln, Nebraska. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Wichita State’s Sydney McKinney (25) leaps to snag a fly ball for an out in the first inning of a game against Nebraska on Thursday, Feb. 3, 2022, at Bowlin Stadium. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Matthew Herron (L) and girlfriend Taylyn Davey enjoy an early birthday picnic for Davey on Thursday, Feb. 3, 2022, at Holmes Lake. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Charuth Van Beuzekom, who owns Shadow Brook Farm and Dutch Girl Creamery with husband Kevin Loth, enjoys the company of a day-old kid in the barn on Tuesday, March 1, 2022. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

North Platte SP’s Jayla Fleck (left), Tonja Heirigs, and Ashton Guo (right) celebrate a three-pointer during a Class D boys state basketball game on Wednesday at Bob Devaney Sports Center, Wednesday, March 9, 2022. SAVANNAH HAMM, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Felipe Gonzalez-Vazquez talks with his attorneys Nancy Peterson (left) and Candice Wooster during his trial for the murder of Lincoln Police Investigator Mario Herrera, Tuesday, March 8, 2022, in Platte County District Court. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

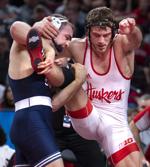

Penn State’s Max Dean upends Nebraska’s Eric Schultz during the 197 championship match of the Big Ten wresting championship matches at Pinnacle Bank Arena on March 6, 2022, in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Top Journal Star photos for March

Spinach grows in a covered tunnel at Shadow Brook farm on Tuesday, March 1, 2022. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Reach the writer at 402-473-7254 or [email protected].

On Twitter @LJSPeterSalter