Kansas City-based firm to lead design of Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge expansion |

OMAHA — A Kansas City-based infrastructure design firm will lead the design of a project meant to connect the Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge with north downtown.

The North Downtown Riverfront Connector Bridge, also known as the “Baby Bob,” will expand downtown Omaha’s iconic 3,000-foot pedestrian bridge. The project is meant to increase access between north downtown and the riverfront.

With City Council approval Tuesday, the city will pay up to $235,411 to HNTB Corporation for design engineering services related to the project.

The North Downtown Riverfront Connector Bridge is planned to span Riverfront Drive and the Union Pacific Railroad tracks, connecting the 13-year-old Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge to a point near the intersection of 10th and Mike Fahey streets.

Eppley Airfield construction plans include consolidating security checkpoints

After viral first edition, Josh Fight sequel planned for May in Lincoln

The “Baby Bob” Pedestrian Connector Bridge would connect major destinations in north downtown, including TD Ameritrade Park, CHI Health Center Omaha and Creighton University, according to plans outlined by the City of Omaha.

With the completion of “Baby Bob,” pedestrians would be able to walk onto the connector bridge just north of the event center and east of the baseball stadium. It’s now about a 20-minute walk to reach the Missouri River bridge from that location if pedestrians go south around CHI Health Center.

City settles lawsuit over alleged asbestos exposure at Pershing Center

Top Journal Star photos for March

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraska’s Griffin Everitt is congragulated by teammates Lei Brice Matthews and Luke Jessen after hitting a 3-run RBI against New Mexico State in the third inning at Haymarket Park on Tuesday, March 15, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Bryan Health staff pray during a ceremony to mark the two-year anniversary of COVID-19 on Tuesday, March 15, 2022, at Bryan East Campus. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraska fans cheer for free T-shirts in the second inning of a game against Omaha on Monday, March 14, 2022, at Haymarket Park. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Malaya Burks (left), 15, plays basketball with his brother DeShawn Burks, Monday, March 14, 2022, at Normal Boulevard & South Basketball Courts. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

The Nebraska women’s basketball team reacts during their bracket announcement Sunday at the Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Elkhorn North celebrates their championship victory over Omaha Skutt after the Class B girls championship Saturday, March 12, 2022, at Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Humphrey/LHF’s Ethan Keller celebrates after his team scores three against Grand Island CC in the fourth quarter during the Class C-2 boys championship at Pinnacle Bank Arena on March 11, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Lt. Col. Christopher Perrone (R), of Papillion, hugs his daughter, Faith, 21, during a welcome home event for soldiers of the Nebraska National Guard’s 67th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade on Friday, March 11, 2022, at the Nebraska Army National Guard base. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Lincoln Lutheran fans react in the closing minutes of the regulation of the Class C-1 girls championship game against North Bend Central, Friday, March 11, 2022, at Pinnacle Bank Arena. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Falls City SH’s head coach Doug Goltz talks to his team between periods during a Class D-2 boys semifinals game Thursday at Devaney Sports Center. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

A pedestrian and a cyclist cross a snowy Goodhue Boulevard on Thursday, March 10, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

People watches the debate to allow concealed handgun without a permit from the balcony, Thursday, March 10, 2022, at Nebraska State Capitol. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Auburn’s Marcus Buitrago (23) tries to control the ball as Fort Calhoun’s Carsen Schwarz (33) dives during a Class C-1 boys semifinal game Thursday at Pinnacle Bank Arena. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

North Platte SP’s Jayla Fleck (left), Tonja Heirigs, and Ashton Guo (right) celebrate a three-pointer during a Class D boys state basketball game on Wednesday at Bob Devaney Sports Center, Wednesday, March 9, 2022. SAVANNAH HAMM, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Felipe Gonzalez-Vazquez talks with his attorneys Nancy Peterson (left) and Candice Wooster during his trial for the murder of Lincoln Police Investigator Mario Herrera, Tuesday, March 8, 2022, in Platte County District Court. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

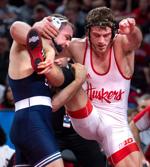

Penn State’s Max Dean upends Nebraska’s Eric Schultz during the 197 championship match of the Big Ten wresting championship matches at Pinnacle Bank Arena on March 6, 2022, in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraskans for Peace hosts a rally in support of Ukraine on Sunday, March 6, 2022. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraska’s Liam Doherty-Herwitz competes on the still rings during the gymnastics meet between Illinois, Minnesota and Nebraska on Saturday, March 5, 2022, at Devaney Sports Center. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Supporters of the Midwest Freedom Convoy line up along the Superior Street bridge over I-80, on March 4, 2022, in Lincoln, Nebraska. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Wichita State’s Sydney McKinney (25) leaps to snag a fly ball for an out in the first inning of a game against Nebraska on Thursday, Feb. 3, 2022, at Bowlin Stadium. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Matthew Herron (L) and girlfriend Taylyn Davey enjoy an early birthday picnic for Davey on Thursday, Feb. 3, 2022, at Holmes Lake. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Charuth Van Beuzekom, who owns Shadow Brook Farm and Dutch Girl Creamery with husband Kevin Loth, enjoys the company of a day-old kid in the barn on Tuesday, March 1, 2022. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Spinach grows in a covered tunnel at Shadow Brook farm on Tuesday, March 1, 2022. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

A driver in a pickup truck makes their way along a northern portion of 27th street as a break in the clouds after Tuesday’s storm allows for a final burst of color on March 22, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Elton John points to the crowd after he finishes his opener, “Bennie And The Jets,” on Sunday, March 27, 2022, during the Elton John: Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour at the Pinnacle Bank Arena. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraska head baseball coach Will Bolt talks with his team between innings during the baseball game on Sunday, March 27, 2022, between Michigan and Nebraska at Haymarket Park. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Cass Warren, 12, throws a disc golf next to his father Dan Warren on a windy afternoon at Pioneers Park, Friday, March 25, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Theresa Thibodeau, Breland Ridenour, Charles Herbster, and Brett Lindstrom (from left) participate in a discourse during a gubernatorial debate hosted at the Nebraska Public Media studios on March 24, 2022. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Lincoln Pius X’s Ellie Wolseger rests on the mat after an attempt in the girls pole vault on Thursday, March 24, 2022, during the Northeast Relays track meet at Lincoln High. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Kindergartener Lyum Brady eats lunch on Wednesday, March 23, 2022, at Hartley Elementary School. GWYNETH ROBERTS, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

A Lincoln city crew cleans up a fallen tree near 15th and Sumner streets, Tuesday, March 22, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Cars travel at the intersection of O and 16th streets on a rainy night, Monday, March 21, 2022. JUSTIN WAN, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

As the sun goes down, fans watch during the baseball game Friday, March 18, 2022, between Nebraska and Texas A&M-Corpus Christian at Haymarket Park. JAIDEN TRIPI, Journal Star

Top Journal Star photos for March

Updated

Nebraska’s Isabelle Bourne and Gonzaga’s Yvonne Ejim dive after a loose ball in the first quarter during the first round of the NCAA Tournament at the KFC Yum! Center on March 18, 2022, in Louisville, Kentucky. KENNETH FERRIERA, Journal Star